If you’re considering various investment options for your retirement plan, purchasing an annuity can help you meet your retirement objectives. Before you purchase an annuity, you will want to understand various aspects, which are outlined below.

Table of Contents

History and Evolution of Annuities

Purposes of Annuities

Accumulation & Payout

Types of Annuities

Immediate Annuity

Deferred Annuity

Variable Annuity

Indexed Annuity

Fees: Surrender Charges, Mortality Fees, etc.

Annuities are Not for Everyone

Introduction to Annuities

There are more than 78 million living Americans who were born after World War II from 1946 to 1964 (baby boomers), and every day in the United States, 10,000 people celebrate their 60th birthday.

The good news is that Americans are living longer than ever. The challenge is that the average person retiring today must plan for a retirement that will last 15 to 20 years. For some, retirement will last 30 years or more. Retirees must deal with the following issues.

- The cost of living is escalating.

- People are living longer and healthier lives.

- Social Security may not be able to meet its long-term obligations.

- More years in retirement and less federal support will mean greater reliance on personal assets to meet the financial needs of retirement.

- Most people may not realize how much they need to save to maintain their current standard of living during retirement.

- Many retirement accounts have been decimated by the economic downturn and may take years to recover.

This uncertainty regarding life after retirement has thrust annuities forward as a solution.

Evolution of the Modern Annuity

Though its history extends back to the days of the Roman Empire, the annuity was not always used for retirement planning purposes. Indeed, the very concept of retirement is relatively modern, evolving as it did only since the industrial revolution. During the 17th and 18th centuries, for example, the annuity principle was the basis of the tontine system in England. Looking for revenues to fight its wars with France, the English government let English investors purchase shares of an annuity plan (tontine) that provided participants with annual payments for life.

The tontine system proved faulty in several key respects, not the least being the fact that the group participant who outlived all others amassed considerable wealth at the expense of deceased participants. Reforms of the tontine system in the mid-1700s would lead to the development of the earliest forms of group annuity contracts.

Group vs. Individual Annuity Contracts

Throughout the 19th century, annuities were only available through group contracts; individuals who were not part of an eligible group were unable to purchase annuities. The first U.S. individual insured annuity was issued in 1912, but the safety and guarantees that are the bedrock of an insured annuity held little appeal until the Great Depression of the 1930s. Sales of deferred annuities took off during this trying decade, and have remained strong ever since.

As the popularity of annuities grew in the 1930s, so, too, did the Internal Revenue Service’s interest in these financial instruments. With no standard definition to measure against, various types of life insurance arrangements were being administered as annuities. A 1939 court case yielded a definition of annuity that is commonly used today:

“In our opinion, an annuity may be described as a sum paid yearly or at other specified intervals in return for the payment of a fixed sum by the annuitant. The annuity itself is the totality of the payments to be made under the contract.” [Bodine v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 1939]

Development of the Deferred Annuity

The earliest individual annuities were immediate annuities, purchased with a (usually substantial) single premium to provide income payments beginning immediately. The deferred annuity evolved out of the need, in some cases, to postpone the annuity starting date.

There are many reasons why an individual might want to postpone the annuity starting date (ASD). For example, the beneficiary of a large inheritance might not need the income right now, and might wish to postpone annuitization (that is, the irrevocable conversion to payout mode) for several years or more. Individuals who didn’t have substantial sums of money, on the other hand, sought ways to use the annuity as a way to accumulate retirement savings. Whatever the reason, the need was the same: Hold off the annuity starting date.

The individual deferred annuity soon followed the introduction of the individual immediate annuity. All annuity contracts—deferred as well as immediate—had one thing in common: annuity starting dates that were, for all practical purposes, inevitable. The contract’s ASD could be deferred, but annuitization itself was not optional. Owners could advance the contract’s ASD to an earlier date, but they could neither postpone the ASD nor surrender the contract for its cash value. Deferred annuities remained this way until the early 1970s.

The Surrender-able Deferred Annuity

The 1970s were a time of great change for retirement savings in America. Arguably the most important and certainly the most far-reaching event to impact retirement savings was passage of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), a sweeping pension law that took major steps towards protecting workers’ pension interests.

ERISA created the notion of personal responsibility for one’s retirement income security, evidenced in part by its creation of the individual retirement account (IRA). Today, of course, retirement savings is widely accepted as the personal responsibility of every American.

The U.S. Tax Code permits a variety of financial products to be used in funding an IRA, including mutual funds and bank certificates of deposit as well as deferred annuity contracts. There is no provision in the Tax Code preventing owners from moving their IRA funds from one account or institution to another; in fact, IRA providers must accommodate an owner’s request to transfer (or roll over) funds from one IRA to another. This put the traditional deferred annuity, with its virtual prohibition against surrender, at a distinct disadvantage. To meet the anticipated demand for individual qualified savings instruments, insurers essentially refitted their deferred annuities to include more reasonable terms for surrendering the contract.

Introduced in 1973 in anticipation of ERISA, the earliest surrenderable deferred annuities were not attractive by today’s standards. To discourage surrender, many contracts included a permanent surrender charge that could be avoided only through annuitization. Still, this was a dramatic development that changed the way consumers saw annuities and insurance companies marketed them.

Tax-deferred growth became a much more widely promoted benefit of the deferred annuity. IRAs (including those funded by deferred annuities) featured tax-deferred growth, but only deferred annuities could claim tax-deferred growth outside of an IRA. Additionally, deferred annuities were not encumbered by the contribution limits imposed on IRAs.

The Variable Annuity

A significant milestone in the history of the modern annuity was the advent of the variable annuity in 1952. Created expressly as a way to maintain a level standard of living on a fixed income in retirement, the variable annuity brought a new investment perspective to the annuity.

Conceptually similar to the mutual fund model of collective investment, variable annuities became extremely popular with consumers in the 1980s and 1990s. The fall in stock prices that began in 2000 hit variable annuities as hard as it did mutual funds and all other equity-based investments. Variable annuity sales dropped in the first few years of the new millennium, but have stabilized and are showing signs of renewed interest by consumers, particularly baby boomers.

The recent experience of falling values underscores the importance of ensuring that prospective customers fully understand the investment risks inherent in variable annuities before investing in them. The consumer who fully understands the risks that are inherent in all equity-based investments, knows the importance of (and practices) diversification, and has a sufficiently long investment horizon to at least consider investing in a variable annuity. If the consumer fails any of these preconditions, though, a variable annuity may be inappropriate.

Annuities Today Cover Accumulation and Income Security Needs

Over the years, annuities have evolved in different ways so that there are now annuity products to suit many different needs. Features have been added that have increased the flexibility and popularity of annuities: some contracts provide checkbook access to funds and others have special death benefits for deferred annuity owners who die before the annuity starting date. There are costs to these features, of course, which make it important for insurance agents and brokers to disclose all contract charges when recommending the purchase of any form of insured annuity.

Today, annuities are flexible enough to permit their use as a long-term accumulation vehicle for almost any need, though a need for income that cannot be outlived remains a primary reason for buying an annuity.

Purposes of Annuities

Annuities possess a benefit unknown to other types of financial vehicles: a payout you cannot outlive.

Distribution of a Lifetime Income

Suppose that you had a sum of money with which to support yourself for the rest of your life. If you spent too much each month, you would run out of money while you were still alive.

If you spent too little, you would not maximize the use of that money—you would die before you had used it up. An annuity eliminates this uncertainty by converting a sum of money into a series of periodic payments that is guaranteed to last a lifetime (or longer).

The first illustration demonstrates how an accumulated retirement fund can be converted to a future income stream via the annuity.

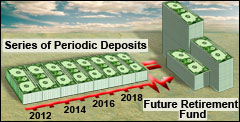

Accumulation of a Retirement Fund

What if the consumer doesn’t have a sum of money for a retirement fund? The annuity can also be structured to allow for the accumulation of such a fund over time, before distribution of the fund begins in the payout period.

Let’s say that you don’t need a lifetime income right away but that you will at some point in the future. Suppose further that you don’t have a large sum of money on hand to pay for an annuity. By setting aside a little bit of your current income, you could accumulate over time a sum of money that could eventually be converted into a stream of lifetime income payments, as shown in the second illustration.

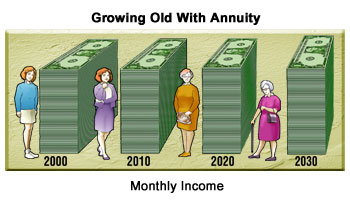

The Risk of Outliving One’s Savings

Let’s take a few minutes to consider why consumers find annuities so appealing. Like all insurance, annuities are designed to alleviate a risk that consumers face: in this case, the risk of outliving your savings.

We all hope to live to a ripe old age. But the longer we live, the thinner our financial resources become, until eventually our life savings may be depleted.

The annuity allows us to transfer part of the financial risk of outliving our assets to an insurance company. So, an annuity is similar to automobile or homeowner’s insurance in that the insurance company absorbs, in exchange for a fee called a premium, a personal risk that each of us has.

The annuity assures that our monthly income continues undiminished as we age.

When an insurance company takes on an annuity risk, it assumes the potential burden of making annuity payments for a very long time. This could be 10 years, 20 years, 30 years, or even longer, depending upon the life span of the annuitant(s).

Advances in medical research, procedures, and technology can be expected to continue. This means simply that people will, on average, be living longer. Insurers who commit today to pay annuity benefits in the future can only estimate what these medical advances will do to the average life span.

Types of Annuities

While every insured annuity contract has an annuity starting date, that does not mean every annuity converts a sum of money into annuity payments right away. The ASD may be immediate, but it may also be deferred for many years. An annuity contract that converts a lump-sum payment into a stream of income right away is called an immediate annuity. A contract that defers the annuity starting date is a deferred annuity.

The Immediate Annuity

An immediate annuity starts payments as soon as the insurance contract is issued. Because an annuity contract cannot simultaneously accept premiums and pay out income benefits, the applicant can only purchase an immediate annuity with a single premium.

The annuity’s income payment cycle is usually monthly, although quarterly, semi-annual, and annual payment cycles are allowed. Technically, payments are made at the end of the payment cycle; for example, an immediate annuity that is to pay income benefits monthly would make the first payment 30 days following the issuance of the contract. Nevertheless, the process of converting the principal sum to payout mode begins as soon as the contract is issued, so the term immediate is appropriate.

As noted previously, the decision to annuitize a sum of money becomes irrevocable once payments begin. Annuity benefits include an insurance element that provides the assurance of lifetime payments (possibly over two lives, in joint and survivor cases). The insurance company must be able to count on the assets paid for the annuity to meet its future obligations to this and all similar contracts; to allow annuitants to cancel their annuity benefits for a refund would open the door for adverse selection against the insurer. Agents and brokers have a responsibility to ensure that their customers fully understand the irrevocability of annuitization.

Suitability

It is possible to avoid insurance charges by merely liquidating a sum of money over a specified period of time without regard for the possibility of outliving assets. The decision to annuitize a lump sum of money should only be made after the annuity owner understands there is a charge for the insurance protection. Ultimately, the suitability of an annuity purchase hinges on whether the buyer sees value in the cost of the insurance protection that is a natural part of the insured annuity.

The issue of suitability is especially important when dealing with senior citizens. By their very nature, seniors tend to trust and believe those who present themselves as experts, and their fear of outliving their money makes them willing to accept the argument that annuities are the only way to guarantee income for life. However, the fact is that while annuities are the only way to guarantee a level income for life, there are other ways to stretch a sum of money for an individual’s lifetime.

While there is no guarantee that payments will remain level, these other distribution methods tend to produce more income (for a given sum of money) than annuitization does. The lower income produced by annuitization is the consequence of the insurance charges by which guaranteed level income payments are made possible. Disclosing this fact is an essential part of the agent or broker’s responsibility to his clients.

The Deferred Annuity

An insured annuity contract that defers the ASD to a future date is called a deferred annuity. Deferred annuities may be purchased with a single lump-sum premium (much like an immediate annuity) or they may be purchased with periodic premium payments. Deferred annuities are useful anytime an individual anticipates wanting to annuitize a sum of money, though not at the present time.

Why a Deferred Annuity?

There are many reasons why an individual might want a deferred annuity. In preparing to retire, for example, individuals may realize a substantial capital gain upon moving down to a smaller home or condo. For many baby boomers now approaching retirement, this will constitute an important (if not their only) source of retirement income.

Rather than convert the money to income payments now, some individuals may decide to wait a few years, until they stop working entirely, to annuitize. Holding the funds in a deferred annuity achieves three things:

- It allows the principal sum to grow larger, on a tax-deferred basis.

- It produces a larger income amount per premium dollar because of the annuitant’s older age at annuitization.

- It provides the owner with time to decide how he wants to use the principal before making a possibly irrevocable decision.

In a few years, annuitizing the contract will provide more income than would be the case with annuitizing immediately.

However, annuitizing immediately would produce a longer period of income payments than would be the case with deferring annuitization, and the sum of benefits paid could be more with an early ASD if the annuitant dies prematurely. Determining which approach makes the most sense can be done only after careful consideration of the ultimate purpose for the annuity, the owner’s need for immediate income, and even the annuitant’s general state of health.

The Deferred Annuity Starting Date

A deferred annuity matures when it reaches the annuity starting date selected by the contract owner. The annuity starting date can be any time up to a maximum age stated in the annuity application and contract. Age 85 is commonly the maximum ASD, but few individuals actually wait until then to begin taking distributions.

If the individual is looking for the flexibility to decide when he wants to annuitize the contract, most financial advisors recommend selecting the latest age possible (for example, 85). One may always annuitize the contract ahead of the ASD, but once that date is reached the insurer is obligated to annuitize the contract.

Suitability

For the various reasons, previously mentioned, it is generally deemed inappropriate to recommend deferred annuities to individuals who are age 60 or older unless the intent is to annuitize the principal in a reasonably short period of time.

For younger individuals, deferred annuities may be suitable for long-term accumulation purposes even if the ultimate use for the money is not yet certain. Tax-deferred growth can make the deferred annuity an attractive long-term accumulation vehicle even if the money is ultimately used for a purpose other than guaranteed lifetime income.

Unless there is a clear intent to annuitize at the end of the deferral period, using a deferred annuity for short-term accumulation purposes is inappropriate in almost any situation. Short-term can be loosely defined as the longer of 10 years or the annuity contract’s surrender charge period. Besides facing a possible surrender charge, short-term surrenders face potential adverse tax consequences-most notably, a possible 10% penalty tax on distributions before age 59½.

Variable Annuities

By the early 1950s, post-war life expectancies were rising alongside the notion of retirement as something more than a brief interlude between work and death. As people began thinking of retirement as lasting 10 years or more, the need for annuity income that would keep pace with inflation over the long term became more and more evident. In 1952, one variable annuity was created as a way to maintain a level standard of living on a fixed income in retirement.

Conceptually similar to the mutual fund model of collective investment, variable annuities became extremely popular with consumers in the 1980s and 1990s. The fall in stock prices that began in 2000 hit variable annuities as hard as it did mutual funds and all other equity-based investments. Variable annuity sales dropped in the first few years of the new millennium, but have since stabilized as investors re-evaluated their acceptance of investment risk.

Variable annuities give annuity contract owners the option of directing where their premiums and account values should be invested. Variable annuity policies offer several separate accounts into which contract owners can direct their money. (The term separate account identifies that monies in these accounts are separate from the insurer’s general account.)

The insurer does not guarantee separate account funds, either in capital growth or interest return. As an equity-based investment, variable annuities (like all forms of variable insurance contracts) are subject to SEC and FINRA jurisdiction and oversight. Agents and brokers who sell variable annuities must be properly registered with FINRA, as well as hold the appropriate insurance license.

The investment risk that is such a critical aspect of the variable annuity demands full disclosure before this type of contract is sold, or even recommended, to individuals. FINRA rules and regulations, as well as the California Insurance Code, require agents and brokers to make clear to prospective customers the risk of loss that is inherent in these types of investments.

Indexed Annuities

While the variable annuity was developing popularity, developments in the fixed interest annuity made it more popular, too. The traditional interest-sensitive deferred annuity provided little basis for contract owners against which to measure their contracts’ current interest rate. To alleviate that uncertainty insurance companies developed the interest indexed annuity. It was probably inevitable that the insurance industry would carry the index concept into the equity market, given the equity market boom of the 1980s and 1990s.

Interest-Indexed Annuities

The interest-indexed annuity evolved out of the need for a way to objectively determine a deferred annuity’s interest rate. Traditional deferred annuities had already evolved to the interest-sensitive platform, but contract owners had little way to know if the rate their contracts were earning were truly reflective of current rates.

With an interest-indexed annuity, the contract’s interest rate is pegged to a published index, such as 10-Year Treasury notes. Typically, interest-indexed annuity interest rates were set a specified level below the index rate. For example, a contract with a 2% spread and a 4% minimum guarantee would credit the annuity account with 4% interest until the index rate was greater than 6%, at which point the interest credited would equal the index rate minus the 2% spread.

The spread between the index rate and the credited rates is partly designed to provide the insurance company with profit, but it serves another important purpose. The spread is a hedging technique that helps protect insurers when market rates rise or fall rapidly.

The typical interest-indexed annuity imposes no limit on the extent to which interest rates can change from one year to the next. This is good news for contract owners when market rates are rising, but when rates fall this becomes an obvious disadvantage. Most interest-indexed annuity contracts include a minimum guaranteed rate (for example, 3-4%) that offers some downside protection.

Most interest-indexed annuities terminate the index at the end of the contract’s surrender period. The reasoning behind this is that contract owners become free to surrender their annuity and move the money elsewhere if the insurer fails to remain competitive in the interest credited.

Accumulation & Payout of an Annuity Contract

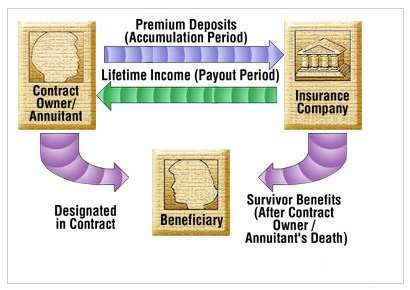

Like an insurance policy, an annuity is a contract between a purchaser and an insurance company. The purchaser pays the premium and generally is the contract owner (sometimes referred to as the policyowner). The contract owner has certain rights under the contract. For example, the contract owner names the annuitant, who is the person who will receive lifetime payments from the annuity. Usually, the contract owner and the annuitant are the same person, as in the following animation. The contract owner also names a beneficiary, who receives any survivor benefits payable under the annuity upon the death of the contract owner/annuitant.

The Accumulation Period

The common feature of all annuities is the distribution of a lifetime income. However, that happens down the road, often after the contract has been in force for some time. So, let’s back up and take things in chronological order.

Most annuities have an accumulation period. In fact, there will always be an accumulation period unless the purchaser already has a lump sum with which to buy the annuity contract and the purchaser wants the payout to begin right away. The accumulation period is initiated by the purchaser’s payment of a premium to an insurance company.

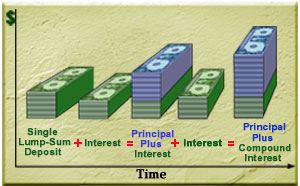

In all types of annuities, during the accumulation period, the purchaser’s payment of a premium (i.e. the principal) earns interest and the principal-plus-interest combination earns more interest in the next year and thereafter. This is what is known as compound interest; that is, interest is earned on interest. The annuity’s accumulation period can begin with the payment of a single lump sum or the first of several periodic premium payments. The growth of an annuity with a single premium deposit is demonstrated by the following illustration.

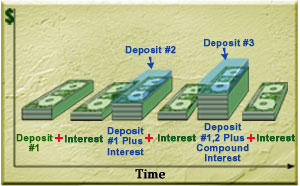

The benefit of compound interest with annuities can also be seen when the accumulation period begins with the first of a series of premium payments. In this case, the interest earned on the original principal in the first year is added to the original principal and the second year’s deposit going into year two. Interest is compounded when in year two, this combined sum earns interest. The growth of an annuity with a series of premium deposits is demonstrated by the following illustration.

That brings us to an important point. The interest earned by the annuity contract is not currently taxed as it is with most savings investment vehicles. Instead, if an individual owns the annuity, the interest is generally not taxed until it is paid out of the contract. Meanwhile, during the accumulation period, this untaxed interest goes right on earning even more interest, which is also untaxed currently and added to principal. This tax advantage is an important reason why people buy annuities.

The Payout Period

Now, we reach the point in time at which we wish to begin using the accumulated money—not all at once, just enough of it periodically so that we can live comfortably.

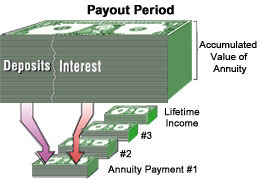

Each periodic annuity payment can be considered a blend of our deposits and the interest those deposits have earned. In the next illustration, we see funds flowing out of both the principal deposits and the interest accumulation to make up each annuity payment. That is exactly how the federal income tax laws view annuity payments.

But wait a minute. Because we don’t know how long we’re going to live, how do we know how much we can take out every now and then and still be assured of having some left no matter how long we live?

We don’t. However, we do know from mortality statistics what our average life expectancy is at the time we begin taking out the money. This is based on our age at that time and our sex (unless unisex mortality tables are used). We may live longer than this average or die before reaching this average. However, if we pool together with a lot of other people, we know that the law of averages will work over a large number of cases. The person who dies early—before the average life expectancy is up—will leave uncollected benefits for the people who surpass their life expectancy and need extra benefits.

An annuity is a combination of three things: deposits, interest, and mortality factor. Even after the annuitant has exhausted all deposits and interest, the annuitant can still collect annuity payments for life due to the insurer’s acceptance of the longevity risk.

The life insurance company is the organization that allows us to operate our annuity pool. We pay our premium deposits into the company, which credits these deposits with interest earnings and promises to pay us an income periodically for the rest of our lives beginning at some future point. We take the risk that we will die before getting all of our deposits (plus interest) back, and the insurance company takes the risk that we will live to a ripe old age.

Take Note

It is often said that an annuity is the flip side of life insurance. Just as life insurance offers protection against dying too soon, an annuity offers protection against living too long; in other words, outliving one’s income. And just as life insurance creates a fund at death, an annuity liquidates a fund during life.

Fees: Surrender Charges, Mortality Fees, etc.

Like any business, insurance companies exist to make money and earn profits. Life insurance companies are in the business of insuring individuals against the mortality-based risks of dying too soon or living too long. Their experience with actuarial principles and the legal reserve system within which they function make life insurance companies well-suited for the job they do, but the intangible nature of the product sometimes makes it difficult to see how or where insurers “make their money.”

It is important that consumers understand there is a cost for the insurance protection inherent in life annuities just as there are costs for owning life insurance. Though unique qualities distinguish annuity fees from life insurance fees, there are also similarities that are a useful way to understand these costs. A mortality-related survivorship factor stands in place of a mortality charge, but both annuity contracts and life insurance policies have comparable expense charges and both rely on assumptions of future interest earned on the contract funds. Disclosing contract fees and charges to prospective customers is every agent and broker’s responsibility with every annuity recommendation.

Surrender Charge

To discourage their use as a short-term investment (and, in some cases, to offset high first-year interest guarantees), virtually all deferred annuities include a surrender charge for early withdrawals. Surrender charges are sometimes called a deferred contingent sales charge, the term contingent implying that the charge is imposed only upon a certain contingency (that is, contract surrender).

While they vary by insurer, most surrender charge periods last no more than 10 to 15 years, and may be as brief as five or six years. Surrender charges are not imposed if the owner annuitizes the contract during the surrender charge period, and most annuity contracts waive the surrender charge if the distribution is the result of the owner’s death.

The existence of a surrender charge is a primary reason senior citizens are cautioned to carefully consider any decision to purchase a deferred annuity. If the senior’s intent is to buy a deferred annuity to use as a funding source for unplanned medical and long-term care expenses, the surrender charge will make withdrawals in the early years especially expensive. Possible adverse tax consequences compound the problems facing early distributions from a deferred annuity.

Annuities are not for everyone

While annuities play an important role in the retirement plans of millions of people, they are not suitable for everyone. This Definitive Guide on Annuities explored the basic forms of insured annuities and illustrated cases where the product would be an appropriate solution to a need. However, these are insurance contracts at their core, and as such there are various fees and charges that ultimately reduce the net gain realized.

The products described in this guide make the most sense for individuals with either a long-term investment horizon or an immediate need for income that’s guaranteed for life. Viewed in a different perspective, they are very likely inappropriate for anyone who intends to use the annuity as a short-term cash investment, or as a way to pass assets to an heir at death. For seniors, immediate annuities have an obvious role to play in providing retirement security, but their role primarily as an accumulation vehicle should be carefully reviewed and justified.

If you have questions or would like to look at an illustration for your own retirement plan, feel free to reach our team by clicking here.

0 Comments